The Welfare State Is Devoid of Generosity

June 26, 2024

Eric Hammer and Daniel Klein examine the actors in the system of the welfare state—the taxpayers, voters, politicians, pundits and advocates, civil servants, and recipients of welfare-state benefits—to determine whether generosity is present. They contend that the welfare state is devoid of generosity.

"The concept of generosity is not operative, one way or the other, in any of the roles that are essential or distinctive to the welfare state."

"The concept of generosity is not operative, one way or the other, in any of the roles that are essential or distinctive to the welfare state."

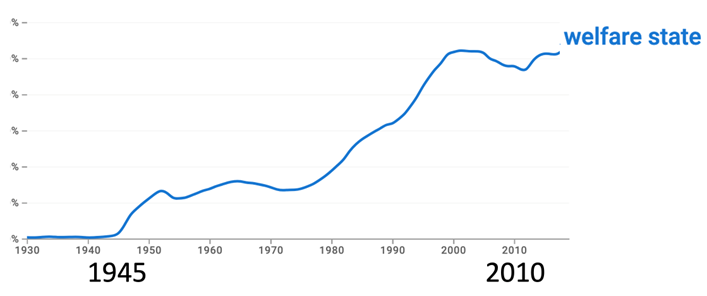

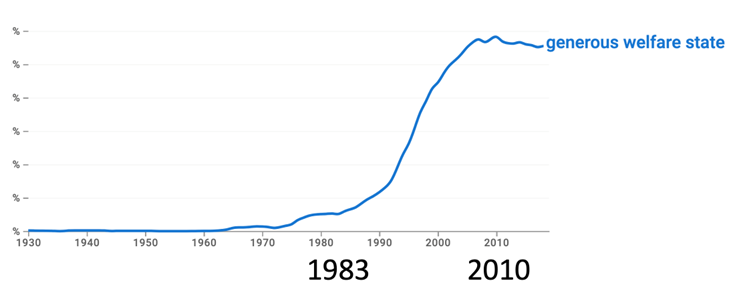

People sometimes speak of “the generous welfare state” or “generous welfare-state benefits.” Such talk might be figurative, to mean abundant as though furnished by generosity. In the figurative expression, it is not that any particular person exhibits generosity, but rather a figurative animism exhibits generosity.

As for actual people, is generosity any part of the welfare state?

In this essay, we use the thought of Adam Smith, particularly The Theory of Moral Sentiments (TMS), to examine the actors in the system—the taxpayers, voters, politicians, pundits and advocates, civil servants, and recipients of welfare-state benefits—to determine whether generosity is present. We contend that the welfare state is devoid of generosity, in the literal sense of the actor acting with generosity.

Also, we do not argue that welfare statism is without virtue or a kind of justice. Apart from our conclusions about generosity, we do not argue against welfare statism—though we’ll confess to not being fans. We suggest that if there is virtue in favoring welfare statism, that virtue is not aptly described as generosity.

Defining the welfare state

What does “welfare state” mean? The definition provided by Wikitionary.com is: “A social system in which the state takes overall responsibility for the welfare of its citizens, providing health care, education, unemployment compensation and social security.”

That definition does not explicitly highlight governmental redistribution of resources, supposedly from richer to poorer. But “welfare state” is often used in that way, and that is how we use it. It is secondary whether the redistribution considered is only means-tested benefit programs or, more broadly most any benefit programs, even universal spending programs, which, given the progressivity of (especially income) taxation, tend to redistribute resources and thereby reduce the material wealth difference between higher and lower. With “welfare state,” we have governmental redistribution in mind.

A main argument for governmental redistribution is that a dollar means more to a poor person than it does to a rich person. Economists call it diminishing marginal utility of wealth. We agree that a dollar means more to a poor person than it does to a rich person; and Smith thought so too. We grant that a person’s marginal utility of wealth is diminishing.

Adam Smith on generosity

Like other human traits and aspirations, virtue has both a singular overall sense and plural facets, parts, or aspects. The virtues most bespoken in TMS are prudence, justice, and beneficence. “Beneficence” is often used broadly to cover all of “the social virtues” (270.10) whose rules are “loose, vague, and indeterminate” (327.1). Generosity is subsumed within beneficence, as are, for example, charity, friendship, and hospitality.

“We never are generous,” Smith writes, “except when in some respect we prefer some other person to ourselves, and sacrifice some great and important interest of our own to an equal interest of a friend or of a superior” (191.10).

That sentence comes in the course of distinguishing generosity from two other virtues. One is humanity, meaning a tenderness or lively compassion toward some other person. Humanity consists in “exquisite fellow-feeling”. “The most humane actions require no self-denial, no self-command, no great exertion of the sense of propriety” (190-91.10). Generosity, by contrast, exerts the sense of propriety and requires self-denial. In the famed example of the man who sacrifices his pinky to stop an earthquake in China, Smith speaks of the sacred sway of the man within the breast: “It is he who shews us the propriety of generosity” (137.4). That’s Smith’s explanation for why “our active principles” are “often…so generous and so noble” (137.4). It is not the “feeble spark of benevolence” (137.4).

The distinction here between humanity and generosity is along the lines of that between the “amiable” virtues and the “respectable” virtues (23–26, 152.34–36). It is in distinguishing generosity from humanity that Smith most notably genders the amiable/respectable distinction: “Humanity is the virtue of a woman, generosity of a man” (190.10).

The other virtue distinguished from generosity is “public spirit.” This too is a respectable (as opposed to amiable) virtue, involving a decision to sacrifice an interest of our own. Public spirit differs from generosity in that the sacrifice is made more to serve the sake of a “public” entity or association, as opposed to particular persons (191–92.11). The distinction is fuzzy, as a social group consists of individual persons and, in turn, is but a part of larger wholes.

Generosity, then, is not merely the rendering of benefit. Motives and causes matter. Smith writes:

The man who, … from proper motives, has performed a generous action, when he looks forward to those whom he has served, feels himself to be the natural object of their love and gratitude, and, by sympathy with them, of the esteem and approbation of all mankind. And when he looks backward to the motive from which he acted, and surveys it in the light in which the indifferent spectator will survey it, he still continues to enter into it, and applauds himself by sympathy with the approbation of this supposed impartial judge. (85.4, boldface added)

Welfare recipients, civil servants, and taxpayers

Smith says that a person is a generous person only if generosity is “the usual and customary disposition of the person.” He allows, however, that an isolated act may be generous even though the person “is not necessarily a generous person” (271.13). Let’s look at the actions that constitute the welfare state and look for generosity.

To effectuate a welfare-state program, it must be conceived and promoted, win support, be embraced and implemented by lawmakers, be paid for by taxpayers, and be administered. And then the benefits must be received.

We present categories of actors. There are some who play a role where the actor’s opinion about the welfare state does not affect what he does in that role. Here we have three categories of actor:

-

Welfare recipients: Generosity is not germane here. Other virtues may be germane to receiving welfare-state benefits, but not generosity.

-

Civil servants: They can do a better or worse job of administering welfare-state programs, but again generosity is not germane. They do not sacrifice an interest of our own to that of others.

-

Taxpayers: A person subject to taxation may choose to avoid or evade some or all of the exactions. One may choose not to comply. But doing so is costly in terms of the trouble of avoidance and the risk of being penalized and punished for evasion. Moreover, a general sense of obligation to conform to such societal conventions is natural and necessary to human being. If paying your taxes involves virtue, the chief virtues involved would seem to be prudence and due regard to certain basic conventions.

Some may think themselves generous in paying their taxes, but perhaps they chicane with their sentiments. Any marginal compliance supplies dollars not to needy people in particular, but to government expenditures generally. And, if one avoids taxes and thereby has on hand an additional $1000, one can then be genuinely generous with it. If generosity were one’s intent, why actuate it by making payments to the government? But no one seems to regard taxpayers as generous, nor those who pay more taxes as more generous than those who pay less. If generosity did induce some marginal compliance, that effect is apparently unobservable to others.

The upshot is that the coerciveness of taxation precludes generosity. There may be an element of public spirit in abiding by basic societal conventions, notably, obeying the government’s laws. But it would be inapt to call the welfare state generous on that basis.

The three foregoing categories—welfare recipients, civil servants, and taxpayers—represent roles. A person in any of those roles may also play other roles where one’s opinion about the welfare state can affect what one does in that role.

Before turning to the remaining categories, we first expound on a general and abstract character in the story: the civic spectator.

The civic spectator

A civic spectator is within each of us. There is no observable activity, no particular muscular effort, essential to the civic spectator, but it is a role that each of us occupies, and our performance in that role stands above our performance in any other role we may occupy.

It is, for the present topic, the role of civic spectator to estimate the welfare state, to assess its merits and demerits, and therefore to judge the welfare state. Estimating is an action, a form of conduct, and therefore a matter of virtue. That virtue corresponds to one sense of the word justice, namely, valuing a given “object with that degree of esteem, or to pursue it with that degree of ardour which to the impartial spectator it may appear to deserve or to be naturally fitted for exciting” (270.10). The object, here, is the welfare state, claims about it, positions on it, and so on.

This sense of justice has been dubbed estimative justice (see chs. 1 and 7 here); it is the matter of estimating objects properly and intellectually pursuing them accordingly. “Objects” includes ideas, sentiments, beliefs, and so on. Smith says that this sense of justice is “still more extensive than either of the” other two senses of justice (270.10).

Virtue is operative for a civic spectator, but the question for us is: Is generosity operative? We answer in the negative. In merely estimating an object, one may arrive at an estimation at odds with other estimations or beliefs that one has, but that is a conflict of beliefs within oneself. It is not a matter of sacrificing an interest of one’s own for the interest of another.

We recognize that estimations may subsequently impel acts of generosity; they may undergird a character of generosity. But generosity is not part of the estimating. Whatever a civic spectator may decide about the welfare state, that conduct remains private and personal; it may be wise and virtuous, or it may be foolish and vain. But it is neither generous nor ungenerous.

With these conclusions about the civic spectator in mind, we turn to the other roles involved in the welfare state.

Politicians, voters, and discoursers

Everyone is affected by his or her own civic spectator. But what about the actions characteristic of politicians, voters, and discoursers? Do we find a generosity that warrants associating generosity with the welfare state?

-

Politicians: Smith may have regarded politicians to be an “insidious and crafty animal[s]” (WN 468.39.), but he would count some as virtuous or public spirited. Among those noted along such lines in TMS are Solon (233.16), Lucius Junius Brutus (192.11), Scipio Nasica (228–29.3), the Duke of Marlborough (251.28), William of Orange (230.6), and Peter the Great (186.11). Indeed, Smith suggested that a “reformer and legislator of a great state” may be “the greatest and noblest of all characters” (232.14), and Ian Simpson Ross (in The Life of Adam Smith) speculated that Smith had George Washington in mind.

Suppose that a politician believes that advancing some welfare-state program promotes the good of the whole of humankind (and, thusly, that it is estimatively just). The civic-spectator facet of our politician holds the welfare state in high estimation. We have already argued that generosity is not operative in the mere role of civic spectator.

Now, we turn to our politician’s conduct in promoting pro-welfare-state reforms. Suppose also that there is a second politician who holds an opposite view on the welfare-state issue; and suppose this second politician acts likewise to promote the reforms that he favors. Are both politicians generous as politicians? If so, then the generosity cannot flow from the welfare state, since, on that very issue, the two generous politicians are at loggerheads.

If, instead, it is suggested that only the pro-welfare-state politician acts generously as a politician, then, again, it must be in the conduct that gives rise to that qualification (i.e., being pro-welfare-state), and that is the conduct of him as civic spectator, where generosity is not operative.

-

Voters: Here, the search for generosity is similar. There may be wisdom and virtue in voting a certain way, but there is very little personal sacrifice in casting a vote, and whatever sacrifice there is is likewise made by those who vote in an opposing fashion. Again, if there is virtue in voting pro-welfare-state, it is the virtue in embracing pro-welfare-state beliefs and hence in the person’s civic-spectator role, not his voter role.

- Discoursers such as pundits and advocates: Here again, the logic is the same. There may be virtue in advocating for certain policies, but whatever sacrifice there is—in expending attention, effort, care to formulate one’s discourse—is likewise made by those advocating in an opposing fashion. If there is virtue in advocating for pro-welfare-state policies, it is the virtue in embracing pro-welfare-state beliefs and hence in the person’s civic-spectator role, not his discourser role.

We have offered a catalog of roles, and it seems to be complete. In none do we find generosity to be operative, and hence none of them provide a basis for associating generosity with the welfare state. Now, we turn to metaphor.

Metaphor and “generous welfare state”

“The house which we have long lived in, the tree whose verdure and shade we have long enjoyed, are both looked upon with a sort of respect that seems due to such benefactors,” writes Smith (94.2). But is a tree a benefactor? Has it been generous? Is gratitude due to it? Smith himself says no (94–96). But he also indicates that it is natural for us to think metaphorically and use terms that follow such metaphors (e.g., 164.4). He often uses figurative or theological language and in his most central notions, such as “man within the breast,” “impartial spectator,” and “invisible hand.” Economic wisdom depends on figurative language (ch. 14 here). Smith uses animisms in his condemnation of slavery (ch. 8 here).

Smith uses an implicit animism when, to signify high or rising wages, he spoke of “liberal wages,” as though in paying higher wages, employers were exhibiting the virtue liberality rather than responding to changing market conditions (WN 565.2). But Smith was not suggesting that employers were exhibiting liberality; rather it was, figuratively, the cosmos that was exhibiting liberality.

In the same fashion, it is natural that high or rising welfare-state benefits might be called “generous welfare state benefits.” That does not refer to any actual human generosity, however. And it does not imply any, as we have seen.

Not all generosity is virtuous

The larger point of the present essay is that the welfare state is devoid of generosity. But it is worth pointing out that generosity is not always virtuous. So, even if generosity were found, such generosity would not necessarily be virtuous.

Generosity can be misdirected and improper. Smith speaks of “a foolish and profuse generosity” (72.2). In An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (WN), he tells of a “useless piece of public generosity” (554.29) and of “the country gentleman” allowing “his generosity” to be imposed upon by scheming “[m]erchants and master manufactures" (WN 267.10; see also 462).

The same goes more broadly for beneficence: Not all beneficence is virtuous. Smith defined distributive justice as “the becoming use of what is as own” or as “proper beneficence”—not any beneficence, but proper beneficence (TMS 269–70.10).

It takes a figure

We conclude that the welfare state is devoid of generosity. The concept of generosity is not operative, one way or the other, in any of the roles that are essential or distinctive to the welfare state.

Nonetheless, “generous welfare state” talk abounds. Such talk can work as figure or metaphor.

But it makes one wonder: Why Isn’t there like talk of “generous industry,” “generous enterprise,” “generous trade,” or “generous markets”?

Eric Hammer holds a PhD in economics from George Mason University. His PhD thesis is titled “Analyzing the Moral Effects of the Welfare State Through the Lens of Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments” (link to abstract), and it provides part of the basis for the present essay. Currently, Hammer is a Sales, Inventory and Operations Planning Manager for a specialty motor manufacturer.

Daniel Klein is professor economics and JIN Chair at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He is the author of Smithian Morals and Central Notions of Smithian Liberalism.

This essay is part of the AdamSmithWorks series Just Sentiments curated by Daniel B. Klein and Erik Matson. New essays will be published on the fourth Wednesday of most months. You can read more about the series in this Speaking of Smith post, "Just Sentiments- Welcome!". Klein and Matson lead the Adam Smith Program in the Department of Economics at George Mason University, in association with the Mercatus Center. In the program, they study big ideas in jurisprudence, politics, ethics, and economics as they were pursued during the original arc of liberalism, especially in the 18th century in Britain.