Pride and Vanity, After Adam Smith

November 27, 2024

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments Adam Smith describes many kinds of men, including the proud man and the vain man. Klein explores Smith's ideas and himself in this essay.

"Smith’s view is that something impels us to learn to command troublesome passions, both solicitous and turbulent, but the commanding necessarily deploys other passions, commanding passions, to command or subdue the troublesome passions. Passions are checked by other passions."

In The Theory of Moral Sentiments Adam Smith describes many kinds of men, including the proud man and the vain man. Klein explores Smith's ideas and himself in this essay.

"Smith’s view is that something impels us to learn to command troublesome passions, both solicitous and turbulent, but the commanding necessarily deploys other passions, commanding passions, to command or subdue the troublesome passions. Passions are checked by other passions."

There is something in Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments that has always hit home with me in an uncomfortable way. It is Smith’s description of the proud man. It comes when Smith compares two vices, pride and vanity. The description of the proud man gives me a feeling of shame, as I recognize myself in it.

Smith’s description of the vain man hits home with me some but less. I feel less liable for my vanity than for my pride.

How about you? Which are you more guilty of, pride or vanity?

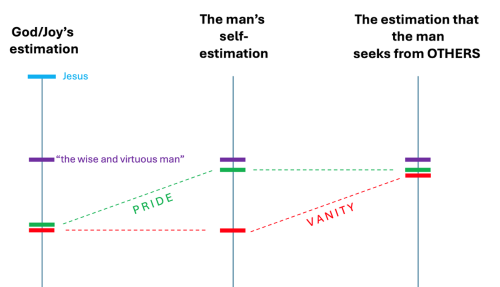

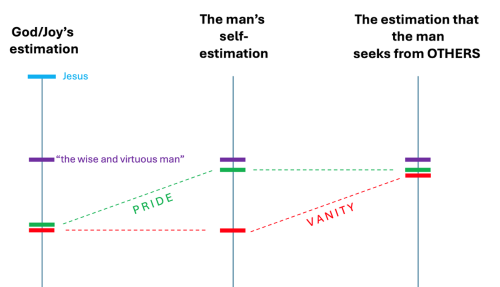

The difference is shown in the following diagram:

The first vertical line registers the individual’s merit or virtue as recognized by God or a God-like being I call ‘Joy.’ Joy is like God in being super knowledgeable and universally benevolent, while other traits of God are not strictly necessary.

The proud man is in green. His estimation of himself is shown on the second vertical line. He over-estimates himself. As Smith put it, “the proud man…thinks much more highly of himself than he deserves” (259.47).

Next is the estimation from others. The proud man “wishes you to view him in no other light than that in which, when he places himself in your situation, he really views himself: he demands no more of you than what he thinks justice” (255.35).

The vain man, in red, however, “wishes that other people should think more highly of him than he thinks of himself” (259.47). For neatness, I put the first two red notches on a level such that our vain man does not over-estimate himself. The third red notch is above that level: The vain man wants you to estimate him higher than he estimates himself.

Before turning to Smith’s descriptions of the proud man and the vain man, consider the man in purple.

The wise and virtuous man

The purple notches represent “the wise and virtuous man.” His character is rare, exceptional among mortals. He wants others to rate him no higher than he thinks he deserves, which is no higher than he does deserve. The three purple notches are on a level. (He is ‘on the level.’)

Still, the wise and virtuous man falls short and knows it:

He feels the imperfect success of all his best endeavours, and sees, with grief and affliction, in how many different features the mortal copy falls short of the immortal original: he remembers, with concern and humiliation, how often, from want of attention, from want of judgment, from want of temper, he has, both in words and actions, both in conduct and conversation, violated the exact rules of perfect propriety, and has so far departed from that model, according to which he wished to fashion his own character and conduct. (247–248.25)

Though the wise and virtuous man will estimate himself as being above some other people, that does not vitiate his conduct:

He…feels so well his own imperfection, he knows so well the difficulty with which he attained his own distant approximation to rectitude, that he cannot regard with contempt the still greater imperfection of other people…. [H]e views it with the most indulgent commiseration, and, by his advice as well as example, is at all times willing to promote their further advancement. (248.25)

And he admires in other people merits that exceed his own:

If, in any particular qualification, they happen to be superior to him (for who is so perfect as not to have many superiors in many different qualifications?), far from envying their superiority, he…esteems and honours their excellence, and never fails to bestow upon it the full measure of applause which it deserves. (248.25)

Smith’s description of the wise and virtuous man, too, hits home with me —

His whole mind, in short, is deeply impressed, his whole behaviour and deportment are distinctly stamped with the character of real modesty; with that of a very moderate estimation of his own merit, and, at the same time, of a full sense of the merit of other people. (248.25)

— because it does not fit me.

The wise and virtuous man compares himself to a character of higher caliber. Mindful of what is higher, he minds how he falls short. Virtue looks up.

The proud man

The proud man, however, compares himself to peers and rivals around him, to whom he thinks himself superior. Vice looks down.

Smith notes that the words pride and proud “are sometimes taken in a good sense” (258.44). Indeed, Smith indicates that pride plays a vital role, as a source of due respect and of resilience in the face of misfortune (147.27, 261.49, 262.52). Also, even the vice of pride has some good sides to it, as indicated in what follows.

Smith’s description of the proud man:

- “If you appear not to respect him as he respects himself, he is more offended than mortified” (255.35).

- “[H]e disdains to court your esteem: he affects even to despise it” (255.35).

- “He seems to wish not so much to excite your esteem for himself as to mortify that for yourself” (255.35).

- “The proud man…never flatters, and is frequently scarce civil to any body” (257.40).

- “He is full of indignation at the unjust superiority, as he thinks it, which is given to [other people]” (257.41).

- “The proud man does not always feel himself at his ease in the company of his equals, and still less in that of his superiors” (256.39).

- “He has recourse to humbler company, for which he has little respect…—that of his inferiors, his flatterers, and dependants” (256.39).

- The proud man is “careful to preserve his independency, and…studies to be frugal and attentive in all his expenses” (256.38).

- “Pride is always a grave, a sullen, and a severe [passion]” (257.41).

- “[The lies] of pride, whenever it condescends to falsehood, are” more serious than white lies (257.41).

- Pride has its pluses, particularly when some feeling of superiority is warranted: “Where there is this real superiority, pride is frequently attended with many respectable virtues—with truth, with integrity, with a high sense of honour, with cordial and steady friendship, with the most inflexible firmness and resolution” (258.42).

- But the proud man lacks upward vitality: “The proud man is commonly too well contented with himself to think that his character requires any amendment. The man who feels himself all-perfect naturally enough despises all further improvement” (258.45).

The vain man

The vain man wants others to estimate him higher than he estimates himself. Smith says that the word vanity is never used as something positive (258.44), but Smith does indicate that vanity may be essential in the process of self-improvement and upward vitality.

Smith’s description of the vain man:

- “When you appear to view him… in his proper colours, he is much more mortified than offended” (255.36).

- “Far from despising your esteem, he courts it with the most anxious assiduity” (255–56).

- “Far from wishing to mortify your self-estimation, he is happy to cherish it, in hopes that in return you will cherish his own. He flatters in order to be flattered” (256.36).

- “He studies to please, and endeavours to bribe you into a good opinion of him by politeness and complaisance, and sometimes even by real and essential good offices, though often displayed…with unnecessary ostentation” (256.36).

- “He courts the company of his superiors as much as the proud man shuns it…. He haunts the courts of kings and the levees of ministers, and gives himself the air of being a candidate for fortune and preferment” (257.40).

- “He is fond of being admitted to the tables of the great, and still more fond of magnifying to other people the familiarity with which he is honoured there: he associates himself as much as he can with fashionable people, with those who are supposed to direct the public opinion—with the witty, with the learned, with the popular… With the people to whom he wishes to recommend himself… he employs…unnecessary ostentation, groundless pretensions, constant assentation, frequently flattery” (257.40).

- “[H]e often reduces himself to poverty and distress long before the end of [his life]” (256.37).

- “[H]e shuns the company of his best friends, whenever the very uncertain current of public favour happens to run in any respect against them” (257.40).

- Vanity has its pluses: “Notwithstanding all its groundless pretensions, however, vanity is almost always a sprightly and a gay, and very often a good-natured passion” (257.41)

- “The worst falsehoods of vanity are all what we call white lies” (257.41)

- “[V]anity [is frequently attended with] many amiable [virtues]—with humanity, with politeness, with a desire to oblige in all little matters, and sometimes with a real generosity in great ones—a generosity, however, which it often wishes to display in the most splendid colours that it can” (258.42).

- The vain man often has capacity for upward vitality, especially in youth: “Vanity is very frequently no more than an attempt prematurely to usurp that glory before it is due. Though your son under five-and-twenty years of age should be but a coxcomb, do not upon that account despair of his becoming before he is forty a very wise and worthy man, and a real proficient in all those talents and virtues to which at present he may only be an ostentatious and empty pretender” (259.46)

- (The foregoing bullet points come in Smith’s contrast between the proud man and the vain man, but Smith had earlier (in time, not in location in the final edition of the book) given a description of vanity, TMS 309–310.8, which is then used in distinguishing “three passions” (1) vanity, (2) love of true glory, and (3) love of virtue. On that threefold comparison, see Figure 24 here.)

If you are a parent, a mentor, a teacher, or an author, here is a tip: “The great secret of education is to direct vanity to proper objects” (259.46).

Pride and vanity mixed

To draw the contrast, Smith compares a man guilty principally of pride and a man guilty principally of vanity. In real life, people are guilty of both:

But the proud man is often vain; and the vain man is often proud… Those two vices being frequently blended in the same character, the characteristics of both are necessarily confounded; and we sometimes find the superficial and impertinent ostentation of vanity joined to the most malignant and derisive insolence of pride. (259.47)

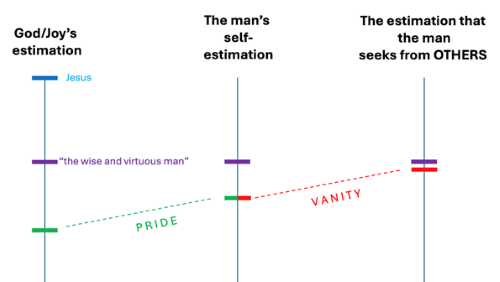

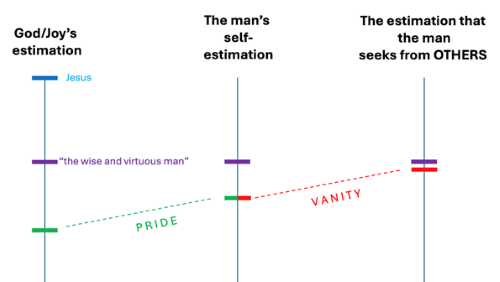

The following figure represents a man who is both proud and vain.

From the mixture of pride and vanity, when we think about another person’s character, “[w]e are sometimes…at a loss…whether to place it among the proud or among the vain” (259.47).

Seduced by a solicitous passion

Pride and vanity are examples of solicitous passions. The solicitous passion are those which “seduce…us from our duty.” The solicitous passions include “[t]he love of ease, of pleasure, of applause, and other selfish gratifications” (238.3, boldface added).

Both pride and vanity stem from a love of applause. The vice of pride is an improper love of one’s own applause, vanity of applause from others. The passion for applause solicits us continually. Smith says that the solicitous passions are “those which it is easy to restrain for a single moment… but which, by their continual and almost incessant solicitations, are, in the course of a life, very apt to mislead into great deviations” (237.2). The solicitous passions “often mislead us into many weaknesses which we have afterwards much reason to be ashamed of” (238.3).

The other set of troublesome passions are turbulent, such as anger and material fear (such as in the face of danger), “which it requires a considerable exertion of self-command to restrain even for a single moment” (237.1). The turbulent passions drive us from our duty, rather than seduce us from our duty.

Pride, vanity, and self-delusion

Smith treats pride and vanity at greater length in the section on self-command than any other troublesome passions. He seems to indicate that they are the most fatal of passions. A weakness to gratify pride and to gratify vanity prompt one into self-deceits, which swell into sustained delusions about worldly affairs and about oneself. How does that happen?

The opinion which we entertain of our own character depends entirely on our judgment concerning our past conduct. It is so disagreeable to think ill of ourselves, that we often purposely turn away our view from those circumstances which might render that judgment unfavourable… Rather than see our own behaviour under so disagreeable an aspect, we…persevere in injustice, merely because we once were unjust, and because we are ashamed and afraid to see that we were so... He is…bold who does not hesitate to pull off the mysterious veil of self-delusion which covers from his view the deformities of his own conduct. (158.4)

Notice that, here, Smith has indicated a solicitous sort of fear: We are afraid—continually—of seeing ourselves in disagreeable aspect. This fear differs from the momentary turbulent sort of fear as when in physical danger.

Were we candid about how unjustly we have believed, spoken, written, and acted, our pride and vanity would be wracked by miserableness. Instead, too often, in weakness, we sustain absurd denialisms. The denialisms sustain delusions and emit caprice. “Vice is always capricious: virtue only is regular and orderly” (225.18).

Commanding passions

Sometimes people say that one’s conduct ought to be governed by rationality, not passions. As I see it, Smith’s view is that something impels us to learn to command troublesome passions, both solicitous and turbulent, but the commanding necessarily deploys other passions, commanding passions, to command or subdue the troublesome passions. Passions are checked by other passions.

Better passions, we hope.

Daniel Klein is professor economics and JIN Chair at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He is the author of Smithian Morals and Central Notions of Smithian Liberalism.

This essay is part of the AdamSmithWorks series Just Sentiments curated by Daniel B. Klein and Erik Matson. New essays will be published on the fourth Wednesday of most months. You can read more about the series in this Speaking of Smith post, "Just Sentiments- Welcome!". Klein and Matson lead the Adam Smith Program in the Department of Economics at George Mason University, in association with the Mercatus Center. In the program, they study big ideas in jurisprudence, politics, ethics, and economics as they were pursued during the original arc of liberalism, especially in the 18th century in Britain.

Daniel Klein is professor economics and JIN Chair at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He is the author of Smithian Morals and Central Notions of Smithian Liberalism.

This essay is part of the AdamSmithWorks series Just Sentiments curated by Daniel B. Klein and Erik Matson. New essays will be published on the fourth Wednesday of most months. You can read more about the series in this Speaking of Smith post, "Just Sentiments- Welcome!". Klein and Matson lead the Adam Smith Program in the Department of Economics at George Mason University, in association with the Mercatus Center. In the program, they study big ideas in jurisprudence, politics, ethics, and economics as they were pursued during the original arc of liberalism, especially in the 18th century in Britain.