Why Read Adam Smith Today? Enduring Insight

After a year-long celebration of Adam Smith's birth in 2023, Peter Boettke addresses those still not well-versed with Smith's magisterial work of political economy.

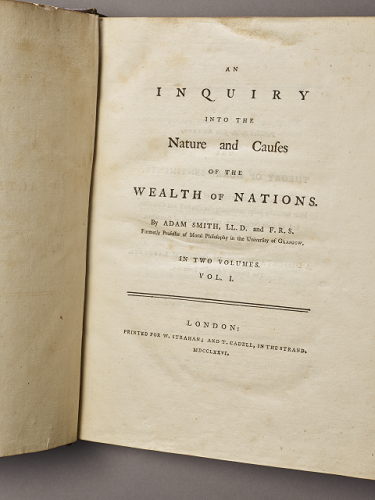

Throughout 2023, the world celebrated the 300th birthday of Adam Smith. Smith is remembered today as the founding father of economic science and a key figure of the Scottish Enlightenment. Smith lived primarily in Scotland throughout his life (1723-1790). He was educated in Glasgow (an experience with teachers he revered) and Oxford (with teachers he viewed with disdain), and he became a Professor of Moral Philosophy upon his return to Glasgow. He achieved international recognition with the publication of The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). However, it is his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) that has earned him immortal fame. It is this work, and its impact throughout the world, that gives reason to the celebration of Adam Smith’s birth three centuries later.

We celebrate the founding figures in scholarly and scientific endeavors fairly frequently. Yet we seldom recommend that young enthusiasts of the discipline, let alone seasoned practitioners, read the works of an individual, except perhaps to satisfy an antiquarian interest. Students of physics are not sent to read Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica (1687), and perhaps not even Albert Einstein’s Relativity (1917). It is generally assumed in modern instruction that whatever was good and true in the ancients is embedded in the modern. All that can be found in the residue of our past scientific and scholarly endeavors is errors, not gems of wisdom, or guidance and insight for our contemporary curiosity and problem solving. But Smith, I will argue, is worth reading to improve our scholarship and science in economics, political economy, and social philosophy today. We still have so much to learn from Smith’s writings.

The iconoclastic economic scholar, Kenneth Boulding, made the case for reading Smith to improve our contemporary practice as clearly as anyone in a classic essay, “After Samuelson, Who Needs Smith?” (1971). Boulding argued we all do because the evolutionary potential of Smith’s ideas has yet to be exhausted. Smith’s insights about how the world works are part of the “extended present”. Science and scholarship do not evolve in a smooth and efficient path from falsehood to truth, but instead in a very jagged and rough-and-tumble process with many influences pulling in one direction or another. Truths are lost, falsehoods are propagated, which means for progress to be made, sometimes we must reach back and re-evolve in a different direction. All that is right and important in Smith has not been incorporated into the scientific consensus that was represented by Paul Samuelson for most of the second half of the 20th century. [1]

The economics profession did not reflect Boulding’s position. From roughly 1950 through the 1980s, the Samuelsonian paradigm dominated the economics profession, and one could reasonably argue that in many ways it still does. The intellectual casualties of this dominance is that both individual purposes and plans of the actors we study, and the institutional environment within which these actors pursue their plans and interact with others was lost in the excessive formalism of the scientific presentation and the excessive aggregation of the scientific approach. Law, politics, and social mores – constant objects of study in Smith’s system – were driven out of scientific investigation in the quest for an “institutionally antiseptic” theory. These core aspects of Smithian political economy and social philosophy had to be rediscovered by Armen Alchian (property rights), James Buchanan (public choice) and Ronald Coase (law and economics). And, of course, it is perhaps not too far a stretch to claim that this counter-revolution in economic science was initiated in the works of F. A. Hayek, such as The Constitution of Liberty (1960), Law, Legislation and Liberty (1979), and The Fatal Conceit (1988). Hayek in the 1940s already saw the scientific writing on the wall and made a two-pronged argument dealing with the methodology of the social sciences on the one hand, and the institutional level of analysis on the other. My purpose here, however, is not to discuss Hayek’s contributions, but Smith’s enduring contribution to our science.

So, who needs Adam Smith today? We all do, because his works still communicate to us how to do political economy humanely and productively, and reminds us of the insights the discipline offers for understanding the human condition in all its variety and complexity. As Hayek (1948) once put it, Smith’s work still surpasses all the modern tomes in social psychology in examining what makes human beings tick and what makes human society possible.

My argument is simple: we can usefully read Smith for his insights into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations; for his wisdom related to moral and political philosophy, and for his guidance in pursuing the liberal plan for liberty, equality and justice. In this essay, I will explore the first of these three reasons to read Smith.

Adam Smith’s Insight

In his notebooks that resulted in The Wealth of Nations, Smith argued that “peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice” were the prerequisites for economic growth and development. The source of the wealth of nations did not reside in the characteristics of the people, nor in the geographic location of the nation, but in the institutional and social ecology within which peoples found themselves interacting with each other and with nature. The differences between people, as Smith would later stress in his example of the philosopher and the street porter, is not as great as the philosopher often assumes. And while hostile terrain and difficult to navigate water-ways, Smith recognizes, raise the costs of transactions, they are not determining factors. No, the prerequisite for Smith, as his good friend David Hume argued in his A Treatise on Human Nature (1739) was the establishment of a system of property, contract and consent to ensure security of person and possession, the transference of property by consent, and the keeping of promises. In short, no taking without a corresponding giving. The foundation of economic progress and the improvement in the human condition is to be found in that fundamentally human propensity to truck, barter and exchange. Smith was not blind to the darker side of our nature, as stressed by Thomas Hobbes. In fact, most of human history was characterized by such a violence trap. But in that violence trap, while there might be conquest and confiscation, there was no wealth creation and generalized human betterment. Peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice – that is what evolves once we get out of the violence trap.

The mechanics of economic development follow directly from Smith’s analysis. In modern language, the only way to increase real income is to increase real productivity. To Smith, as he argues in the first sentence of his great book, the greatest improvement in the productive capacity of mankind is due to the refinements in the division of labor. But in Smith's discussion of the division of labor, we are immediately confronted with the details of what is involved with increasing real productivity. This is achieved through the improvement in the physical capital with which individuals are able to work with. Time saving machines are tinkered with until they are useful by young boys who are seeking only to get the job done faster so they can play with their friends, as well as by the great innovators and creators of the dawn of the industrial age. Human ingenuity leads to productivity enhancing tools and techniques. Real productivity is also improved through the development of human capital – knowledge and skill. In modern economics we focus on education as the primary vehicle for the acquisition of human capital, but in Smith’s day the primary vehicle was learning by doing.

Smith also put forth the proposition that the division of labor was limited by the extent of the market. Teasing out this proposition one can see that as trade expands and the scale and scope of the market extends, more refinements in the division of labor, and the coordination of individuals and their specialized production emerge through commercial transactions based in property, prices, and profit-and-loss. Early in The Wealth of Nations, Smith illustrates this point by asking his readers to contemplate how even the most everyday product – in this instance a common woolen coat – ends up on the back of the day laborer. (see 1776, 22 ff) Smith walks through in a very abstract way all the specialized production and exchanges of the small bits and pieces required to provide the woolen coat. As he says, the number of exchanges exceeds human computation. He concludes this discussion by making the simple observation that the average person in a world characterized by such refinements in the division of labor enjoyed a standard of living that exceeded those of the King in a society where such productive specialization and peaceful social cooperation through exchange could not take place. This Smithian observation remains true to this day when we look at the data either over time or in a comparative way at any moment in time. The essential element in the mechanics of economic development is that set of institutional arrangements --given to us by formal and informal rules, and their enforcement by formal and informal sanctions-- that enable individuals in that society to pursue productive specialization and realize peaceful social cooperation. The meat and potatoes of economic analysis is in the study of exchange and production, what makes possible those processes is the social ecology within which they operate. As mentioned above, one cannot do economics and political economy properly without putting an emphasis on the analysis of law, politics and society as the indispensable framework for the study of economic lives.

The problem with assuming this background rather than analyzing its origins, fragility, or persistence, is that what gets assumed often gets forgotten – e.g., a fish doesn’t recognize the water it swims in. Instead, what Smith had developed – as Lionel Robbins argued in his The Theory of Economic Policy in British Classical Political Economy (1952) – was a political economy grounded in the institutional analysis of development. Economic life, to Smith, never existed in a vacuum. Private property and freedom of contract protected by the rule of law all evolved as economic theory was evolving in the work of the British classical political economists. And, as James Buchanan (1968, 5) would later argue, we as analysts can never be content with simply assuming the institutional background of commercial society, but must from the ordinary behavioral postulates of economic analysis derive that institutional framework itself. In doing so, we will be able to build a genuine institutional economics that, in combination with the core structure of economic theory, will be able to reconstruct a political economy worthy of Adam Smith for our modern times.

Read part two of this essay: Why Read Adam Smith Today? Enduring Wisdom

Want to explore more?

Read part two of this essay: Why Read Adam Smith Today? Enduring Wisdom

Want to explore more?

- Peter Boettke, The Role of the Economist in a Free Society: The Art of Political Economy, at Econlib.

- Read Michael Munger's three-part essay series on the Division of Labor at AdamSmithWorks.

- Samuel Fleischacker, Economics and the Ordinary Person: Re-reading Adam Smith, at Econlib.

- Henry C. Clark on Growth, a Great Antidote Podcast.

- Peter Boettke on Mainline Economics, a Great Antidote podcast.

Peter Boettke is Distinguished University Professor of Economics & Philosophy, George Mason University, MSN 1A1, Fairfax, VA 22030 pboettke@gmu.edu. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the conference “Economy, Society and Culture: Adam Smith’s” at Moscow State University, October 27, 2023. I appreciate the kind invitation to speak from Professor Alexander Maltsev and the constructive and critical feedback from the participants.

Notes

[1] I think it might be relevant to stress to contemporary readers that Boulding was no lone wolf howling in the wilderness. He was the 2nd John Bates Clark medal winner (after Samuelson), and he stood in juxtaposition to Samuelson from the very start. Boulding (1948) in a review essay on Samuelson’s Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947) argued that Samuelsonian formalism may be too flawless in its precision to aid us scientifically in our quest to understand human sociability and the complex phenomena of modern commercial society. Instead, he suggested that working in the vague and literary borderland between economics and sociology may ultimately prove to be the more scientifically productive path. Subsequent developments of property rights economics, public choice economics, law and economics, economic sociology, New Institutional Economics, and the entrepreneurial theory of the market process all would suggest Boulding was right in his assessment well before the scientific consensus turned in that direction.