Speaking of Smith

What Harriet Martineau Ate: Plum Pudding and Christmas Cakes

By spreading the cost of rare or exotics ingredients over thousands of plum puddings in hundreds of cities, an extravagance can become a reliable once-a-year treat. Renee Wilmeth returns with her delicious combination of intellectual history, food market insights, and kitchen adventure encouragement.

We often take for granted that anything we want is just around the corner or a click away. Ingredients from other countries, specialized tools for creating culinary masterpieces, and even cookbooks can all be delivered within 48 hours. We are so disconnected from the actual source of our ingredients, we often don’t think about how it gets to us or the layers of labor involved.

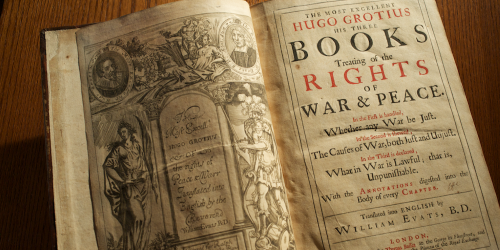

There are some well known examples that try to help us with this. Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil” is a favorite among classical liberals and libertarians (with complementary video of Milton Friedman explaining). A more mainstream example might be Thomas Thwaites’ “Toaster Project”but, as with so many things, Adam Smith did it first with his laborer’s wool coat example. Then, Harriet Martineau, writes her version in her work Illustrations of Political Economy (1832). Martineau explicitly identifies herself as a popularizer of Smith’s economic ideas but where Smith shows us what a man needs when working outside the home, Martineau shows us how the same principles are in the kitchen and the dining room.

In chapter 6 of “Life in the Wilds,” the first story in Martineau’s Illustrations of Political Economy, Mr. Stone and the Captain discuss efficiencies of labor and the Captain notes how many hands are required just to make one of his wife’s delicious Dorsetshire meat pies. Aside from the local input of the cattle, the butter, and assembly of the ingredients, there are hands that touch separately the obtaining of the salt which comes from one source and the pepper which comes from another place entirely. That they are English men and women living in South Africa further increases the challenges that they face.

The pepper must come from over the sea; and only think of all the labour that will cost: the trouble of those who grow and prepare it in another land, the boxes in which it is packed, the ship in which it is conveyed, the waggon which brings it from Cape Town; all these things are necessary to afford us pepper for our plainest pies.

Mr. Stone replies that he can only imagine how expensive a plum pudding would be considering the extensive additional labor at home and abroad. Ingredients for a traditional Christmas pudding, also known as a plum pudding, would include:

- Flour – from the local grist mill, milled by mill workers

- Sugar – imported from the West Indies

- Eggs – local, from backyard chickens

- Suet – beef fat, local

- Dried Raisins – imported as dried fruit

- Dried Currants – harvested locally, then dried

- Dried, candied citrus peel – imported fruit, but the with the peelings candied and dried

- Nuts such as Almonds and Walnuts – depending on location, whatever could be harvested, otherwise, imported

- Spices such Nutmeg, Allspice – imported

Of course, most Christmas puddings would have additional ingredients like apples or carrots to moisten the batter or a wider variety of fruits and nuts (although not necessarily fresh or dried plums!). And a good pudding would be started weeks in advance of a holiday because of another necessity – brandy for soaking the fruits beforehand and aging the pudding before Christmas.

The flour and the butter may be had near home; but the sugar must be brought from one country, and the raisins from another, and the spice from a third, and the brandy from a fourth There could be no plum-puddings without such a division of labour as it almost confuses one to think of. No, indeed; for we must consider, moreover, the labour which has been spent in providing the means of producing and conveying the things which make a plum-pudding. Think of the toil of preparing the vineyards where the raisins grow; of the smith and the carpenter who made the press where the grapes are prepared, and of the miner, the smelter, the founder, the furnace-builder, the bricklayer, and others who helped to make their tools, and the feller of wood, the grower of hemp, the rope-makers, the sail-makers, the ship-builders, the sailors who must do their part towards bringing the fruit to our shores.

At this point a reader might conclude that a plum pudding would be far too expensive for the common worker. But by spreading that cost over thousands of plum puddings in hundreds of cities, an extravagance can become a reliable once-a-year treat. The market can provide the goods even with large and dispersed labor costs.

In Victorian England, traditional plum pudding, also known as Christmas pudding, was prepared weeks in advance of the holiday. If you lived in a city, you might have had easier access to spices and other ingredients but with a little planning and variation, even a rural Christmas pudding would have been delicious!

A traditional plum pudding is packed with dried fruits like raisins and currants as well as candied orange or lemon peel. These are soaked a few days in advance before adding to a batter with spices like nutmeg, cloves, and all spice – all of which would have arrived in Victorian England from exotic locales.

While some traditional ingredients like beef suet may not whet your appetite, a more modern take on traditional Christmas pudding can still combine the classic flavors. This recipe is lighter and easier to prepare, while still honoring the festive spirit and Smith’s market economy insights.

Modern Christmas Pudding

Ingredients:

- 1 cup (150g) mixed dried fruits (raisins, currants, candied dried citrus peel)

- 1/2 cup (75g) chopped dried apricots

- 1/2 cup (75g) dried cranberries or cherries

- 1/2 cup (120ml) freshly squeezed orange juice

- 1/2 cup (120ml) brandy or rum

- 1 cup (150g) fresh breadcrumbs

- 1/2 cup (75g) all-purpose flour

- 1/2 tsp baking powder

- 1 tsp ground cinnamon

- 1 tsp ground nutmeg

- 1/2 tsp ground ginger

- 1/4 tsp salt

- 1/2 cup (100g) light brown sugar

- 2 large eggs, beaten

- Zest of 1 orange

- Zest of 1 lemon

- 1/2 cup (120ml) melted unsalted butter or coconut oil

1. In a bowl, mix the dried fruits, citrus peel, apricots, and cranberries or cherries with orange juice and brandy. Let it soak for at least 2 hours, or ideally overnight, to allow the flavors to meld.

2. In a separate bowl, combine the breadcrumbs, flour, baking powder, spices, salt, and brown sugar. Stir to evenly distribute the dry ingredients. Add the soaked fruit mixture (including any remaining juice), eggs, citrus zests, and melted butter to the dry ingredients. Mix until well combined.

3. Heavily grease with butter a pudding basin, if you have one, or other heatproof bowl that can withstand steaming. You can also use a ceramic baking dish with a lid if it fits in the pot with the boiling water. However, the pudding needs to rise, so ensure there’s enough headspace to let it do so. Pour the pudding mixture into the prepared bowl, pressing it down slightly to avoid air pockets.

4. Cover the top of the bowl with a round of parchment paper and then a piece of aluminum foil with the edges hanging out. Add the lid if you have one. If not, securing the parchment and foil in place with string. Place the bowl in a large pot with simmering water (about halfway up the sides of the bowl), cover and steam for about 3 hours. Check regularly to ensure the water remains simmering.

5. After steaming, remove the pudding from the pot and let it cool. Once cool, remove it from the dish it steamed in and wrap tightly in plastic wrap, then aluminum foil. Store the pudding in the fridge for up to a month if made in advance. (This is called “aging” and lets the flavors meld.)

6. Steam the pudding again for about 1 hour before serving. Turn it out onto a plate and serve warm with brandy butter, custard, or ice cream. For an extra festive touch, you can flambé the pudding with more brandy just before serving.

If you’d like to learn more about Harriett Martineau, please join us for a Timeless Reading Group on later chapters from Illustrations of Political Economy.

More by Renee Wilmeth in her #WhatAdamSmithAte series

What Adam Smith Ate: Apple Charlotte

What Adam Smith Ate: Christmas Punch

What Adam Smith Ate: A Holiday Feast

What Adam Smith Ate: Apple Charlotte

What Adam Smith Ate: Christmas Punch

What Adam Smith Ate: A Holiday Feast

More about the Division of Labor

Part 3 of “An Animal That Trades” Video Series: Division of Labor

Michael Munger’s Division of Labor, Part 1, Part 2: A Beautiful Machine, Part 3: The System of Exchange

Comments

Adam Smith and British Bubbles???

There’s a delightful moment in Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations where he neatly demonstrates the efficacy and efficiency of free trade by talking about wine...

So why are the French buying up vineyard land in England???